South Carolina  SC African-Americans

SC African-Americans  Grave Matters – Introduction

Grave Matters – Introduction  History and Differences Between African-American and Euro-American Cemeteries

History and Differences Between African-American and Euro-American Cemeteries

History of African-American Cemeteries

It might seem that a good place to begin our exploration of African-American cemeteries is in Africa. Understanding how African groups buried their dead might help us better understand the early development of African-American cemeteries here in the Southeast.

This is, unfortunately, much more difficult than you might imagine. Africa is a large continent with many different cultural groups. Many are poorly understood. The

10 to 20 million African-Americans forcefully transported as slaves to the shores of the United States came from a number of different cultures. Further complicating this approach is the interaction of different religious beliefs once the slaves arrived on the plantations – most planters were Christians, while some blacks were Moslems and many others held other religious beliefs.

One anthropologist, Margaret Washington Creel, has examined a range of African beliefs and religious practices in an effort to better understand slave religion. In her study,

"A Peculiar People": Slave Religion and Community-Culture Among the Gullahs, she explores the beliefs of the BaKongo, Ovimbundu, and other groups on the Windward and Gold Coasts.

It is even more difficult to discover the religious beliefs of African-American slaves. Planters were rarely interested and often took steps to curb, or at least carefully monitor, the religious training and activities of their slaves. Very few planter diaries recount the events surrounding slave burials.

Yet we do know that these

African-American slaves died by the thousands. One study, for example, found that the mortality rate of black children on the South Carolina and Georgia coastal rice plantations was astonishingly high – nearly 90% of all children died before they reached the age of 16 years. Even on more interior cotton plantations it is likely that nearly one out of every three slave children died before adulthood. Death was certainly a way of life for African-American slaves and they had ample opportunities to make the trip from slave settlement to cemetery for their friends and family.

Thomas Chaplin, a Sea Island cotton planter on

St. Helena Island in Beaufort County, South Carolina, mentions the making or purchasing of coffins for black slaves on only two occasions. He describes only one African-American burial, on May 6, 1850:

Got Uncle Ben's [slave] Paul to make coffin for poor old Anthony. The body begins to smell very bad already, had it put in the coffin as soon as it came. Buried the body alongside of his son about 11 o'clock at night.... There were a large number of Negroes from all directions present, I suppose over two hundred.

At another nineteenth century South Carolina slave burial reported by Creel:

The coffin, a rough home-made affair, was placed upon a cart, which was drawn by an old Gray, and the multitudes formed in a line in the rear, marching two deep. The procession was something like a quarter of a mile long. Perhaps every fifteenth person down the line carried an uplifted torch. As the procession moved slowly toward "the lonesome graveyard" down by the side of the swamp, they sung the well-known hymn:

"When I can read my title clear

To mansions in the skies,

I bid farewell to every fear

and wipe my weeping eyes."

.... the corpse was lowered into the grave and covered, each person throwing a handful of dirt into the grave as a last farewell act of kindness to the dead.... A prayer was offered.... This concluded the services at the grave.

Yet another slave burial, on

Georgia's Butler Island, was described by Frances Anne Kemble in early 1839:

Yesterday evening the burial of the poor man Shadrack took place.... just as the twilight was thickening into darkness I went with Mr. [Butler] to the cottage of one of the slaves ... who was to perform the burial service. The coffin was laid on trestles in front of the cooper's cottage, and a large assemblage of the people had gathered round, many of the men carrying pine-wood torches .... the coffin being taken up, proceeded to the people's burial ground.... When the coffin was lowered the grave was found to be partially filled with water – naturally enough, for the whole island is a mere swamp, off which the Altamaha is only kept from sweeping by the high dikes all round it. This seemed to shock and distress the people ....

All of these

slave burials are similar. They seem to have invariably taken place

at night, possibly to allow slaves from neighboring plantations to attend, but just as likely because no other time was available. This may help explain why so many African-American burials continued to be held on Sundays even into the early twentieth century. All of the accounts suggest that the burials were rather significant affairs, with prayers, singing, and sometimes even an air of a pageant. Sometimes the service was reported to continue until the morning. Many accounts from the mid- and late-nineteenth century reveal that

African-Americans were uniformly buried east-west, with the head to the west. One freed slave explained that the dead should not have to turn around when Gabriel blows his trumpet in the eastern sunrise. Others have suggested they were buried facing Africa.

Even where the slaves were buried seems similar. All seem to represent

marginal property – land which the planter wasn't likely to use for other purposes. The burial spots have been described as "ragged patches of live-oak and palmetto and brier tangle which throughout the Islands are a sign of graves within, – graves scattered without symmetry, and often without headstones or head-boards, or sticks ...." A more recent researcher, Elsie Clews Parsons, observes that the African-American cemeteries were:

hidden away in remote spots among trees and underbrush. In the middle of some fields are islands of large trees the owners preferred not to make arable, because of the exhaustive work of clearing it. Old graves are now in among these trees and surrounding underbrush.

Frances Anne Kemble reported that while an enclosure was erected around the graves of several white laborers buried on Butler Island, the graves of the African-American slaves were trampled on by the plantation cattle.

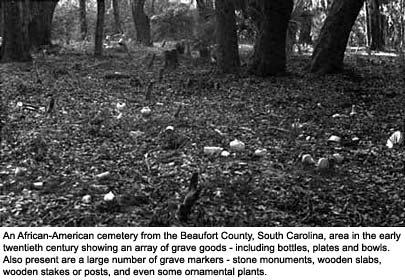

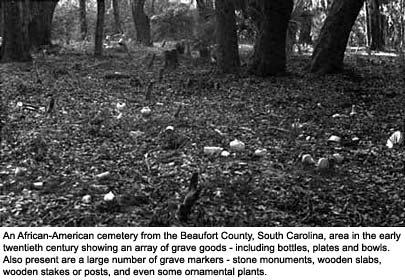

A black cemetery in the South Carolina up country was described by John William DeForest shortly after the Civil War. He commented that while a few marble and brick headstones were present, most were "wooden slabs, all grimed and mouldering with the dampness of the forest...." At the time, some of the wooden slabs had painted names and dates. The paint likely flaked off only shortly before the wood itself rotted away.

Graves were marked in a variety of ways

Graves were marked in a variety of ways besides wood or stone slabs. Sometimes unusual carved wooden staffs, thought perhaps to represent religious motifs or effigies, were used. Some graves were marked using plants, such as cedars or yuccas, and anthropologists have suggested this tradition may reflect an African belief in the living spirit. This tradition can be traced at least to Haiti, where blacks, probably mixing Christian religion with African beliefs, explain that, "trees live after, death is not the end." Yuccas and other "prickly" plants may also have been used "to keep the spirits" in the cemetery. Other graves were marked with pieces of iron pipe, railroad iron, or any other convenient object.

At times

shells were used to mark the grave. One anthropologist in the early 1890s remarked that "nearly every grave has bordering or thrown upon it a few bleached sea-shells of a dozen different kinds." This practice has been traced back to at least the BaKongo belief that the sea shell encloses the soul's immortal presence. There was a prayer to the mbamba sea shell:

As strong as your house you shall keep my life for me. When you leave for the sea, take me along, that I may live forever with you.

Even into the twentieth century some Gullah explained the use of shells on graves as representing the sea:

The sea brought us, the sea shall take us back. So the shells upon our graves stand for water, the means of glory and the land of demise.

Probably the most commonly known African-American grave marking practice was the use of

"offerings" on top of the grave. One of most detailed discussions of this practice is provided by John Michael Vlach, in

The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts. He notes that the objects found on graves included not only pottery, but also "cups, saucers, bowls, clocks, salt and pepper shakers, medicine bottles, spoons, pitchers, oyster shells, conch shells, white pebbles, toys, dolls' heads, bric-a-brac statues, light bulbs, tureens, flashlights, soap dishes, false teeth, syrup jugs, spectacles, cigar boxes, piggy banks, gun locks, razors, knives, tomato cans, flower pots, marbles, bits of plaster, [and] toilet tanks."

This practice may be traced back to Africa, where a wide variety of items used by the dead individual were placed on the grave. Some believe that the symbolism is that of the body destroyed by death. Others trace the practice to a belief that the practice guards the grave, preventing the dead from returning to direct the lives of those still living. Some suggest the symbolism of the various items is particularly important – with reflective items, like glass and mirrors, used to show the "mirror image" of this life compared to the next. Other items focus on water as symbolism, both as representing how African Americans were transported as slaves and also as representing how they will be transported into the next world. A number of the grave goods are also "killed," or deliberately damaged. This is to perhaps help the item to stay in the afterlife with its owner.

In truth, we really don't know the meaning of this practice, although it was recognized by whites at least as far back as Dubois Hayward's day, when he wrote about the practice in the short story, "Half Pint Flask."

Writing in the first quarter of the twentieth century, Elsie Clews Parsons commented that

African-American cemeteries did not typically preserve family groupings. Although generations of related kin would be buried at the same graveyard, the tie was to the location, not to a particular 3 by 6 foot piece of ground. The Bennett Papers, in the South Carolina Historical Society, reveal several stories of African-Americans wanting to be buried in very specific graveyards, although specific plots are never of concern. In one case a black was reported to have specifically warned his friends, "don't bury me in strange ground; I won't stay buried if you do. Bury me where I say." A somewhat similar account is provided in an article from the

Journal of American Folklore. An article recounts the legend of a slave who begged not to be buried in the graveyard of his mean-spirited master. When his dying request was ignored, he found retribution by haunting the plantation.

Creel offers one of the more detailed explorations of African-American beliefs toward death during slavery, noting that many of the spirituals provide rare glimpses of the slaves' belief systems. One, in particular, was especially telling:

I wonder where my mudder gone;

Sing, O graveyard!

Graveyard ought to know me;

Ring, Jerusalem!

Grass grow in de graveyard;

Sing, O Graveyard!

Graveyard ought to know me;

Ring, Jerusalem!

Creel observes that while the anguish is clearly conveyed by this song, so too is a sense of hope – most clearly revealed in the line, "Grass grow in de graveyard." She relates this to the BaKongo tradition that although there is certainly death, there is also life and rebirth. She wonders if the line, "Graveyard ought to know me" is a reference to the many trips slaves took there burying their friends or family, or whether it might have a deeper meaning, perhaps referring to the slaves' previous journeys to the world of the dead as "seekers."

Differences Between Cemeteries

This brief overview of African-American cemeteries has revealed that there are a lot of differences between traditional African-American and traditional Euro-American cemeteries. Some of these differences can be traced to different religious beliefs. Some are probably only the by-product of one group being enslaved by the other.

The location of African-American graveyards in

marginal areas, for example, was probably the result of blacks being enslaved. Not only did owners not want to lose valuable land to slaves, but controlling even where the dead might be buried was yet another example of the power plantation owners had over their slaves.

The

use of plants to mark graves, however, is likely related to African antecedents. Marking the graves was important, regardless of what was used, at least for the current generation. The predominance of temporary items – plants and wood planks, for example – suggests that it wasn't particularly important for future generations to know the location of any specific grave.

In fact, the use of

temporary markers helps, in its own way, to ensure that the cemetery is always available to those who want to be buried with their kin. As one modern black man explained, "there is always room for one more person." This, of course, sounds impossible to many whites, who see cemeteries in terms of a finite number of square feet. But this is simply not how African-Americans have traditionally viewed graveyards.

Cynthia Conner, an archaeologist who studied South Carolina low country plantation cemeteries, remarked that the very

ideology of black and white graveyards is fundamentally different. In white cemeteries, the:

idealization of death is paramount. The romanticization of the landscape is intended to create heaven on earth in the cemetery grounds and deny the blunt reality of death. This is initially accomplished through placement [of the white cemetery] in a favorable location. . . . The setting is further enhanced through the simultaneous control of unrestrained natural growth and the use of a few select trees such as live oaks to create a parklike atmosphere. . . . The black cemetery, on the other hand, is not directed toward a parklike environment, or, I believe, the denial of death.

African-American cemeteries have grave depressions and mounded graves. There is no attempt to make grass grow over the graves or create special vegetation. Trees, typically, are neither encouraged nor discouraged. Cemeteries, as previously mentioned, appear "neglected" or even "abandoned" in contrast to the neat, tidy rows of a white cemetery. The mapping of African-American cemeteries like the two examples previously discussed reveals the somewhat random placement of graves.

Old African-American cemeteries are rarely documented. They infrequently appear on maps and almost never are shown on historic plats. It just wasn't important to most plantation owners to show the location of "slave burial grounds." These graveyards, used for generations by tradition, are rarely delineated by deeds or other legal instruments.

These cemeteries, however, are often well-known to the rural African-American communities. Where traditional historical and documentary sources fail to provide information, often oral history can provide impressive details on the size, number of individuals buried, general locations of different family plots, and old fence lines. Too often, however, these local sources are not sought out.

Grave Matters Articles

Introduction to African-American Cemeteries in South Carolina

Archaeology and African-American Cemeteries

History of African-American Cemeteries

Differences between African-American and Euro-American Cemeteries

Preservation of African-American Cemeteries

Additional Resources