South Carolina  SC African-Americans History

SC African-Americans History  SC Slavery

SC Slavery

This section of our guide to African-American history in South Carolina examines the stages of slavery from capture through purchase. Specifically it looks at where and how Africans were taken into bondage, the middle passage, which brought slaves from Africa to America, and the auctioning off of individuals and families, once the slaves arrived. In all, it outlines the various steps of the slave trade from the shores of Africa to the markets of Charleston, one of the largest slave ports in the world. The essays herein were written for SCIWAY by Michael Trinkley, executive director of the

Chicora Foundation.

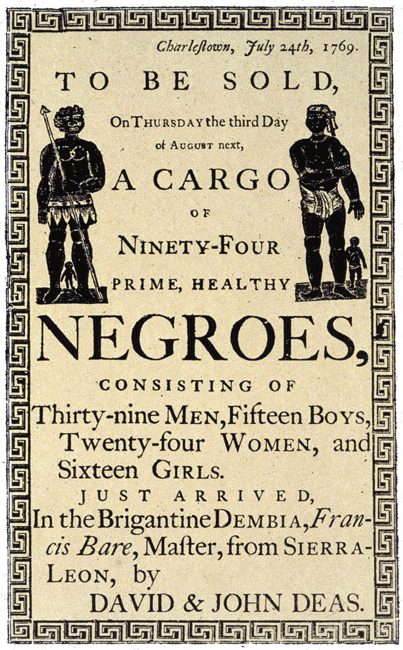

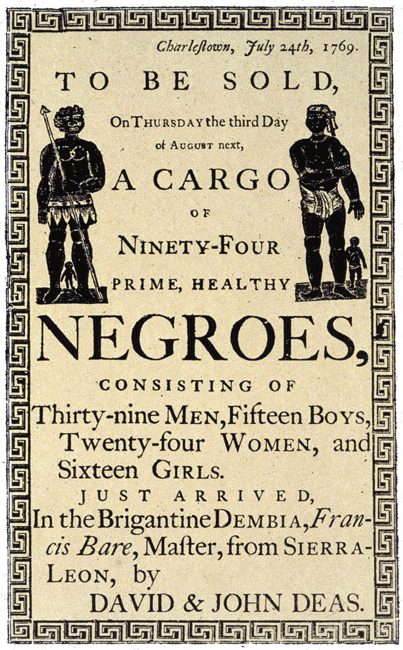

In 1769, the firm of

David and John Deas advertised

the sale of 94 African-Americans in Charleston, SC.

South Carolina's First Slaves – Native Americans

Before we begin to discuss African slaves, however, let us first look at our state's original slaves,

South Carolina Native Americans. These men and women had lived along the rivers of the Lowcountry and among the mountains of the Upstate for thousands of years before the first European settler arrived. As the noted American historian Patrick Minges explains,

No sooner had they set foot on shore near Charleston than [did] the English set about establishing the "peculiar institution" of Native American slavery. Seeking the gold that had changed the face of the Spanish Empire but finding none, the English settlers of the Carolinas quickly seized upon the most abundant and available resource they could attain. The indigenous peoples of the Southeastern United States became, themselves, a commodity on the open market.

How did the Native Americans come to be slaves? The tribes in South Carolina were often at war with one another. In consequence, they learned to hunt down and capture members of enemy tribes, selling them to whites as slaves. Others, of course, were captured and sold by the new settlers directly. In either case, Native Americans made up a large share of South Carolina's seventeenth- and eighteenth-century slave population.

In time, however, white planters began to "phase out" the use of Native Americans on their plantations. For one thing, they had decided that Africans were far better suited to

the back-breaking work of cultivating rice than Indians were. For another, black people seemed to have a stronger resistance to white diseases like small pox and yellow fever. And finally, white people learned that if a Native American slave ran away, they probably weren't going to find him again. Native Americans were all too familiar with the nooks and crannies of "the new world." They knew where to hide, and they knew how to find help. If they could escape, they could take refuge in the midst of a nearby tribe.

Nevertheless, strong ties formed between South Carolina's Native Americans and the Africans who were brought to her shore. These ties were especially strong in regards to religion. Minges points out some of the other bonds Indians and blacks shared:

In addition to working together in the fields, they lived together in communal living quarters, began to produce collective recipes for food and herbal remedies, shared myths and legends, and ultimately intermarried. Apart from their collective exploitation at the hands of colonial slavery, Africans and Native Americans possessed similar worldviews rooted in their historic relationship to the subtropical coastlands of the middle Atlantic.

If you are interested in learning more about South Carolina's Native American slaves, you may want to read Minges' article in full. It is called

All My Slaves, Whether Negroes, Indians, Mustees, or Molattoes, and

you can find it by clicking here.

South Carolina and the African Slave Trade

As with Native Americans, Africans were often sold into slavery by enemy tribes. More commonly, however, tribes sold their own members to Europeans as punishment for an infraction or crime, including such offenses as murder, theft, or treachery against the tribal king. Still other tribes sold members when forced to by famine or debt. Whatever the reason, African kings were implicit in the slave trade and profited from it.

Slavery was established in the New World by the Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch, all of whom sent African slaves to work in both North and South America during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The English began aggressively trading in what was called

"black ivory" during the middle of the seventeenth century, spurred on by the need for laborers in the hot, humid sugar fields on the West Indian islands of Barbados, St. Christopher, the Bermudas, and Jamaica.

By the time Charles Towne was settled in 1670, Englishmen from the West Indies were well acquainted with slavery and the huge profits they could reap from the toil of others. Slavery was therefore considered an essential ingredient in the successful establishment of cash crop plantations in South Carolina.

Like other European nations, England created a commercial entity, the

Royal African Company, to underwrite the slave trade. A string of forts and "slave factories" were established from the Cape Verde Islands to the Bight of Biafra. But the slave trade would likely not have been as "successful" were it not for the "unholy alliance" between the English (and other European nations) and the African kingdoms on whose territories the forts stood. The English slave traders did their best to dupe the native kings, and each native king did his best to obtain the maximum amount of goods in exchange for the slaves he had for sale.

The slave traders discovered that Carolina planters had very specific ideas concerning the ethnicity of the slaves they sought. No less a merchant than Henry Laurens wrote:

The Slaves from the River Gambia are preferr'd to all others with us [here in Carolina] save the Gold Coast.... next to Them the Windward Coast are preferr'd to Angolas.

In other words, slaves from the region of Senegambia and present-day Ghana were preferred. At the opposite end of the spectrum were the "Calabar" or Ibo or "Bite" slaves from the Niger Delta, who Carolina planters would purchase only if no others were available. In the middle were those from the Windward Coast and Angola.

One of the reasons South Carolina planters wanted slaves from the coastal regions of Africa was that they already knew how to grow rice. In fact, rice cultivation had been an integral part of coastal African culture since 1500 BC.

The Middle Passage

For their cargoes of human flesh, the traders brought iron and copper bars, brass pans and kettles, cowrey shells, old guns, gun powder, cloth, and alcohol. In return, ships might load on anywhere from 200 to over 600 African slaves, stacking them like cord wood and allowing almost no breathing room. The crowding was so severe, the ventilation so bad, and the food so poor during the

"Middle Passage" of between five weeks and three months that a loss of around 14 to 20% of their "cargo" was considered the normal price of doing business. This slave trade is thought to have transported

at least 10 million, and perhaps as many as 20 million, Africans to the American shore.

The Auction Block – How Slaves Were Sold

After their horrific Middle Passage, over 40% of the African slaves reaching the British colonies before the American Revolution passed through South Carolina. Almost all of these slaves entered the Charleston port, being briefly quarantined on Sullivan's Island, before being sold in Charleston's slave markets.

Carolina planters developed a vision of

the "ideal" slave – tall, healthy, male, between the ages of 14 and 18, "free of blemishes," and as dark as possible. For these ideal slaves Carolina planters in the eighteenth century paid, on average, between 100 and 200 sterling – in today's money that is between $11,630 and $23,200!

Sylvia Cannon, a freed slave, described slave auctions this way:

I see 'em sell plenty colored peoples away in them days, 'cause that the way white folks made heap of their money. Course, they ain't never tell us how much they sell 'em for. Just stand 'em up on a block about three feet high and a speculator bid 'em off just like they was horses. Them what was bid off didn't never say nothing neither. Don't know who bought my brothers, George and Earl. I see 'em sell some slaves twice before I was sold, and I see the slaves when they be traveling like hogs to Darlington. Some of them be women folks looking like they going to get down, they so heavy.

The slave auctioneers spoke of their business as though they were, in fact, buying and selling horses. The callousness is clear in this July 10, 1856 letter from slave trader A.J. McElveen to Charleston slave merchant Z.B. Oakes:

I offered Richardson 1350 [equal to 27,000 in 1998] for his two negros. He Refused to take it. The fellow is Rather light. He weighs 121 lbs., but Good teeth & not whipped. The little Girl he was offrd 475 [9,500, 1998]. I thought the boy worth about 850 [17,000, 1998] and at that price they would not Sell for cost, but I Supposed the fellow would bring 9 to 950 [18,000 to 19,000, 1998] &c and the little Girl 500 [8,300] at best.

Edmund L. Drago's book,

Broke by the War: Letters of a Slave Trader, includes additional letters describing the nonchalance of those dealing in "the bodies and souls of men." (University of South Carolina Press, 1991)

The Price of a Human Being

And what was the value of these human beings that South Carolina planters and merchants traded in? Prices can be calculated from bills of sale, inventories, and other historic documents. In addition, at least one "price table" has been located. From the early 1850s, it was found in the Tyre Glen papers and applies to the Forsythe County area of North Carolina. The amounts listed reflect nineteenth-century dollar values.

| Age |

Value |

| 1 |

100 |

| 2 |

125 |

| 3 |

150 |

| 4 |

175 |

| 5 |

200 |

| 6 |

225 |

| 7 |

250 |

| 8 |

300 |

| 9 |

350 |

| 10 |

400 |

| 11 |

450 |

| 12 |

500 |

| 13 |

550 |

| 14 |

600 |

| 16 |

650 |

| 17 |

750 |

| 18 |

800 |

|

| Age |

Value |

| 19 |

850 |

| 20 |

900 |

| 21 |

875 |

| 22 |

850 |

| 23 |

825 |

| 24 |

800 |

| 25 |

775 |

| 26 |

750 |

| 27 |

725 |

| 28 |

700 |

| 29 |

675 |

| 30 |

650 |

| 31 |

625 |

| 32 |

600 |

| 33 |

575 |

| 34 |

550 |

| 35 |

525 |

|

| Age |

Value |

| 36 |

500 |

| 37 |

475 |

| 38 |

450 |

| 39 |

425 |

| 40 |

400 |

| 41 |

375 |

| 42 |

350 |

| 43 |

325 |

| 44 |

300 |

| 45 |

275 |

| 46 |

250 |

| 47 |

225 |

| 48 |

200 |

| 49 |

175 |

| 50 |

150 |

| 55 |

100 |

| 60 |

50 |

|

Other documents, however, make it clear that the price of a slave was variable. Slaves were often divided into classes, such as

- Number One Men (19-25 years old)

- Fair/Ordinary Men

- Best Boys (15-18 years old)

- Best Boys (10-14 years old)

- Number One Women

- Fair/Ordinary Women

- Best Girls (10-15 years old)

- Women with One or Two Children

- Families (also called "fancies" or "scrubs")

An 1857 account reveals these values:

| Class |

Value in Dollars, 1857 |

Value in Dollars, 1998 |

| Number 1 men |

1250-1450 |

20,800-24,100 |

| Fair/Ordinary Men |

1000-1150 |

16,700-19,200 |

| Best Boys (Age 15-18) |

1100-1200 |

18,300-20,000 |

| Best Boys (Age 10-14) |

500-575 |

8,300-17,900 |

| Number 1 Women |

1050-1225 |

17,500-20,400 |

| Fair/Ordinary Women |

1050-1225 |

14,200-17,100 |

| Best Girls |

500-1000 |

8,300-16,700 |

| Families |

"sell in their usual proportions" |

The Separation of Families

Southern slave dealers and plantation owners defended their practices, claiming that separations of families were rare and that when they did occur, there was little hardship. South Carolinian Chancellor Harper argued that blacks lacked any capability for domestic affection and showed, "insensibility to ties of kindred." In other words, African-Americans didn't mind being bought and sold since they were naturally promiscuous and lacked the ability to achieve stable family life.

As an old former slave, Jennie Hill, explained,

Some people think that slaves had no feeling – that they bore their children as animals bear their young and that there was no heart-break when the children were torn from their parents or the mother taken from her brood to toil for a master in another state. But that isn't so. The slaves loved their families even as the Negroes love their own today and the happiest time of their lives was when they could sit at their cabin doors when the day's work was done and sang the old slave songs, "Swing Low Sweet Chariot," "Massa's in the Cold, Cold Ground, " and "Nobody Know What Trouble I've Seen." Children learned these songs and sang them only as a Negro child could. That was the slave's only happiness, a happiness that for many of them did not last.

And another ex-slave, Savilla Burrell, remembered the heartache this way:

They sell one of Mother's chillun once, and when she take on and cry about it, Marster say, "Stop that sniffing there if you don't want to get a whipping." She grieve and cry at night about it.

How many slaves were sold away from their families? One study,

Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South by Michael Tadman, suggests that one out of every five marriages was prematurely terminated by sale and that if other interventions are added, the number rises to 1 in 3. In addition, slave trading tore away one in every two slave children under the age of 14.