South Carolina  SC African-American History

SC African-American History  1968 Orangeburg Massacre

1968 Orangeburg Massacre

What Happened at the Orangeburg Massacre?

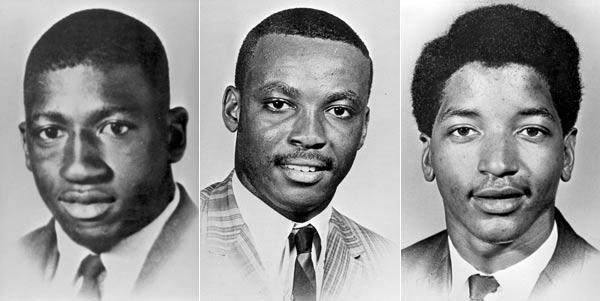

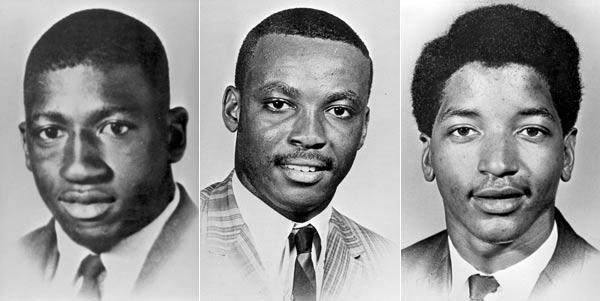

On the night of February 8th, 1968, three students – Samuel Hammond, Henry Smith, and Delano Middleton, who was still in high school – were killed by police gunfire on the South Carolina State College (now University) campus in

Orangeburg. Twenty-eight others were wounded. None of the students were armed and almost all were shot in their backs, buttocks, sides, or the soles of their feet.

(Delano Middleton, Samuel Hammond, Jr, and Henry Smith)

(Delano Middleton, Samuel Hammond, Jr, and Henry Smith)

Tensions between students and police had gradually escalated over a period of three nights, following efforts by students to desegregate

All Star Bowling in downtown Orangeburg. The bowling alley was owned by Harry K. Floyd, who claimed that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not apply to his establishment because it was private. However, because the alley operated a lunch counter, it fell under the jurisdiction of laws regulating interstate commerce and thus federal desegregation.

( All Star Bowling by Andy Hunter, 2014 © Do Not Use Without Written Consent )

( All Star Bowling by Andy Hunter, 2014 © Do Not Use Without Written Consent )

Although many black and white members of the community had tried to persuade Floyd to integrate, he refused. Appeals to the US Justice Department also went unheeded, and on the evening of Monday, February 5th, a group of roughly 40 South Carolina State students, led by senior John Stroman, entered the alley. Floyd denied them the right to play, and after the police arrived, the students returned to campus.

On Tuesday night, Stroman tried again. This time, he and other students were met by 20 police officers who initially barricaded the bowling alley's locked door. Once the door was opened, Stroman and over 30 others entered the premises, where they remained for just under half an hour. In acknowledgement of the brewing tension, Pete Strom, longtime chief of the State Law Enforcement Division (SLED), had been dispatched to Orangeburg to try to maintain peace. After speaking with Strom, Stroman asked the female students to go home and advised all remaining protesters to leave if they did not want to be arrested.

Fifteen students chose to stay, hoping their arrests would compel the issue's resolution in court. As they were led to waiting patrol cars, an angry crowd gathered outside the bowling alley. New recruits arrived from campus, and some of the incoming students armed themselves with bricks obtained from a nearby construction site. An intervention by Henry Vincent, South Carolina State's Dean of Students, secured the release of the jailed students, including Stroman, who returned to the parking lot. The scene settled until a firetruck, ordered by police chief Roger Poston, arrived. A newcomer to Orangeburg, Poston was unaware that local students had been sprayed with firehoses at a 1960 sit-in. At this point, fear and a sense of betrayal swept the young crowd, despite pleas from Stroman, who climbed onto a car to calm fellow demonstrators.

( Troops March Through Orangeburg before Massacre | Bill Barley, 1968 )

( Troops March Through Orangeburg before Massacre | Bill Barley, 1968 )

By then, at least 50 (some say as many as 100) law enforcement officers were present, many brandishing truncheons. Both Poston and Stroman made repeated calls for calm, but it was too late; the seeds of riot had been sown. Three to four hundred students rallied, and a surge of angry youngsters pressed against the bowling alley's storefront, hurling insults and fists. The troopers responded with broad-scale beatings. One young man's skull was cracked, and reports from that night bear witness to at least two female students being held down and clubbed by officers. Wounded and enraged, the students broke windows out of cars and four buildings during their retreat.

Wednesday, February 7th, passed in a haze of whispers and waiting. Classes on campus were cancelled, and students met to plan a protest march for later that day. Permits were sought but denied by Mayor E.O. Pendarvis and the City of Orangeburg. Instead, white officials and businessmen came to campus, but their lack of support – and in some cases their obvious disdain – further fueled the students' dissent. Together with their professors, the student body compiled a formal list of grievances and presented them at City Hall late that afternoon. The list asked for 12 items, a third of which focused on injustices within the local medical community. For example, number five asked that "the Orangeburg Medical Association make a public a statement of intent to serve all persons on an equal basis, regardless or race, religion, or creed." Number nine asked leaders to "encourag[e] the Orangeburg Regional Hospital to accept the Medicare Program." Along with All Star Bowling, Orangeburg Regional Hospital remained segregated in spite of federal law.

( Tanks Line up in Orangeburg before Massacre | Bill Barley, 1968 )

( Tanks Line up in Orangeburg before Massacre | Bill Barley, 1968 )

As the hours progressed, both South Carolina State and Claflin were placed on lockdown. By Thursday, February 8th, roughly 120 armed National Guardsmen, state highwaymen, and local policemen had amassed at the edges of South Carolina State's campus. An additional 450 troops were stationed downtown. The officers were issued shotguns loaded with double-ought buckshot, used to kill deer and other large game.

Even now, those present in Orangeburg that winter speak of the eerie calm that descended upon the community. They also recall the brutal temperature. Dean Livingston, longtime editor of Orangeburg's daily paper, the

Times and Democrat, later said, "And cold, it was cold. One of the coldest nights, I think, I can recall in my life."

That night as darkness fell, students at South Carolina State gathered on a hill at the school's entrance, holding hands and singing. At 10 PM, they lit a bonfire. Thirty minutes later, firemen moved in to douse the blaze, backed by just under 70 officers. The students began to retreat, but someone threw either a banister or a rock, hitting a highway trooper named David Shealy in the face. Shealy fell to the ground bleeding. Another officer fired his gun in the air as a warning. Later claiming they feared the shot had been fired by a student, eight other officers and a city policeman opened fire.

( Wounded in the Orangeburg Before Massacre | Bill Barley, 1968 )

( Wounded in the Orangeburg Before Massacre | Bill Barley, 1968 )

In all, the onslaught the ensued lasted from 8 and 15 seconds. Between 100 and 150 students were present. Of these, 31 young black people were shot, three of whom died. Samuel Ephesians Hammond, Jr. and Henry Ezekial Smith, ages 18 and 19 respectively, were students at South Carolina State. Delano Herman Middleton, age 17, was a senior at nearby Wilkinson High School.

Middleton was not involved in the protests. His mother worked as a maid on campus, and he often stopped there on his way home from basketball practice. In all, he was shot seven times, once in the heart. Henry "Smitty" Smith, an ROTC student and native of

Marion, was shot three times, including in his neck. "Sam" or "Sammy" Hammond was a freshman from

Barnwell who was studying to be a teacher. He was shot in the back and died on the floor of Orangeburg's segregated hospital. Also killed was the unborn child of Louise Kelly Cawley, age 27, one of the young women beaten during the protest at All Star Bowling. Cawley suffered a miscarriage the following week.

Aftermath of the Orangeburg Massacre

The following day,

Governor Robert McNair held a press conference in

Columbia. McNair had been elected a year earlier with 99% of the state's black vote, and while he called it "one of the saddest days in the history of South Carolina," he also degraded the shootings as an "unfortunate incident" and bemoaned the fact that the Palmetto State's "reputation for racial harmony [had] been blemished."

Operating on inaccurate news reports, McNair said the incident occurred off-campus and placed blame on "black power advocates":

The years of hard work and understanding have been shattered by this unfortunate incident at Orangeburg. Our reputation for racial harmony has been blemished by the actions of those who would place selfish motives and interests above the welfare and security of the majority.

Although McNair personally asked the FBI to conduct an investigation the morning after the shootings, he did not mandate a state investigation. Chief Strom was a close colleague of then-FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, and the bureau's efforts to bring justice have been widely maligned. Strom was employed at the will of McNair, and he was never indicted. McNair acknowledges culpability in

his 2006 biography, where he accepts responsibility for the events of that night. Decades later, he continued to lament the effect the massacre had had on the white law enforcement officers present, saying, "They are heartbroken and distressed over what happened."

Although the Orangeburg Massacre took place just two years before Kent State, it did not receive widespread national attention, in part because early stories blamed students and outside agitators, and in part because the young people involved were black instead of white. Cleveland Sellers, a 23-year-old

Bamberg County native who served formerly as a program director for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was arrested on riot charges. Two-and-a-half-years later, he was convicted and sentenced to a year in prison. Conversely, every law enforcement agent involved was acquitted.

Sellers, who had been shot during the attack, was pardoned in 1993 – nearly 25 years later – after evidence proved he was innocent. In the intervening years, he earned his master's degree from Harvard and his doctorate from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. For eight years, he served as the president of

Voorhees College (Update: became Voorhees University in April 2022), located in his hometown of

Denmark, before stepping down in 2016 due to failing health.

South Carolina has never officially investigated the events surrounding the Orangeburg Massacre, and some say this lack of resolution prevents a painful wound from healing in our state. Although multiple attempts have been made to open a state investigation, and to honor February 8th as an annual day of remembrance, South Carolina's state legislature has refused to vote on the measure. In the words of the former chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Jim Harrison, "I would like to know what it will accomplish. If it will help move South Carolina forward, I'm all for it. If it's simply going to dredge up the past and wrongdoings, then I don't see what good it's going to do."

In 2007, the FBI declined to reopen the federal investigation as well. Although both governors

Jim Hodges and

Mark Sanford issued public statements of regret for the shootings and deaths, none of the nine officers involved have received even an informal reprimand.

Modern Responses to the Massacre

In February of 2003 – 35 years after the Orangeburg Massacre – Governor Mark Sanford officially apologized for the tragedy, stating, "I think it's important to tell the African-American community in South Carolina we don't just regret what happened in Orangeburg 35 years ago, we apologize for it."

Following this acknowledgment, numerous attempts have been made to gain a state investigation, reopen the federal investigation, and create a day of remembrance. Thus far, all such efforts have failed. Use the links below to learn more about them:

- SC College Marks 'Orangeburg Massacre' Anniversary

In February 2001, Governor Jim Hodges said, "We deeply regret what happened on the night of February 8, 1968." This was the first official concession of remorse by the State of South Carolina for its role in the Orangeburg Massacre.

- Governor Mark Sanford Apologizes for Orangeburg Massacre

While Governor Sanford did not attend the 2003 memorial for the victims of the Orangeburg Massacre, he sent a written statement with South Carolina's first public apology.

- SC Senate Bill S.22

Introduced in January 2007, this bill sought to create a commission to make recommendations to compensate the victims and families of the Orangeburg Massacre.

- SC House Bill H.3824

Introduced in March 2007, this measure would have established a commission to investigate the Orangeburg Massacre and prepare a formal report. Of the bill's 26 sponsors, only one was white.

- FBI Refuses to Reopen Investigation into Orangeburg Massacre

In December 2007, the FBI announced that it would not reopen the case, which acquitted the nine white officers involved in the deaths of three Orangeburg students. In this article, Cleveland Sellers reacts to the decision. A 1970 article by TIME Magazine details significant flaws in the FBI investigation.

- Closure for Orangeburg Massacre

Jack Bass, a witness to the massacre who is now considered its preeminent historian, offers his thoughts on the Orangeburg Massacre and the need for a formal investigation.

- Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968

This thorough documentary uses interviews with the participants, both white and black, to tell the story of the Orangeburg Massacre. It also powerfully documents the ways in which white South Carolina politicians, including such pivotal figures as Earnest "Fritz" Hollings and Robert "Bobby" Harrell, have dismissed efforts to honor the victims or even provide basic answers to lingering questions regarding the murders.

Orangeburg Massacre: Learn More

- All Star Bowling

This segregated Orangeburg bowling alley served as the site of the initial confrontation between students and police. The alley remained in business until 2007.

- 1960 Civil Rights Protest March in Orangeburg

This brief study examines Orangeburg's role in Civil Rights Movement and the events that led, over a course of six years, to the Orangeburg Massacre. These events included a protest march in 1960 where 1,000 Orangeburg students were fired upon with tear gas and full-pressure water hoses, and 300 students were arrested.

- Survivors Tell Their Stories

Watch this video with interviews by several of the survivors of the shooting.

- Documenting the Orangeburg Massacre

This Harvard University report examines what happened the night of February 8th, 1968.

- Orangeburg Massacre Photo Gallery

Explore the people and places involved in the history of the Orangeburg Massacre, from its origins to its aftermath.

- The Orangeburg Massacre

Journalists Jack Bass and Jack Nelson recount the events of February 1968 and their aftermath. This book was first published in 1970 and remains the authoritative source on the Orangeburg Massacre. Both journalists were present at the massacre.

- The River of No Return

Cleveland Sellers wrote this autobiography during his time in prison. He was later exonerated and received a full pardon.